Hunger Never Wears the Same Face: Stories in Seven Portraits

A young man. A widow. A retiree. A nonprofit leader.

Food as a verb thanks

for sponsoring this series

Note to reader: these are fictionalized accounts of real people and experiences.

These seven stories are representative of real interviews, encounters, and reporting over the last 20 years. While these portraits are fictionalized, the people behind them — their details and struggles — are not.

We hope these stories offer a respectful rendering of the people impacted by hunger and its different forms while also spotlighting Chattanooga Area Food Bank, which served nearly 17 million meals across 20 counties in 2024.

This is the first in a two-party story series devoted to addressing regional hunger and Chattanooga Area Food Bank's role in responding to that crisis.

Hunger never wears the same face.

- CJ, a 17-year old male living in South Chattanooga.

Average daily caloric needs: 5,000 calories.

Average daily caloric intake: 3,100 calories.

CJ hasn't eaten a piece of fresh fruit in weeks. The last time was early August, the night of the football jamboree, and some folks from a church he'd never heard of had come to the school with plates of dinner kept warm in tin foil to feed the team.

They brought so much food, it filled three tables, stretched end-to-end-to-end: pasta, beans, rice, banana pudding.

It was the banana in the banana pudding. That was the fresh fruit.

They left it out — little candles burning under the tin foil containers — before, during and after the game. His hunger was like an ache, but only ate eight or nine bites of pasta and only two bites of banana pudding.

Food is a strange thing for CJ. The only time he's seen the kitchen being used is during the winter; the stove door's open and his mom's trying to heat the apartment.

His mom works, but jobs change so much he's never fully sure where. His dad died when he was young, before he could even tie his shoes. The closest thing he has to a trusted adult? His coach and his grandmother. But he's got his own kids and she's got cancer.

Most of CJ's meals come from school cafeteria or fast food or the gas station or dollar store.

None of his meals come with a sense of abundance. CJ can't remember the last time he ever ate without fear.

Fear there won't be enough.

Fear that eating will make him even hungrier.

Psychologists and social workers often use the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) as a study that evaluates trauma and dysfunction. He'd score through the roof.

But CJ doesn't know that. Doesn't know the terms disassociation or complex trauma. He just knows — even barely — that life feels so numb, his head without a body, like a fog that makes him want to sleep and not wake.

CJ has an eating disorder. Normally associated with middle or upper class teens, eating disorders also affect people like CJ: he refuses to eat, afraid that doing so will make him even hungrier.

Each week, Chattanooga Area Food Bank supports food pantries in schools and sack-packs for the weekend. Across 20 counties, the food bank distributes more than 160,000 meals for children and teens each year.

Like CJ.

But it's never enough.

- Kendall, 63, living in Hamilton County.

Approximate average median income: $75,000.

Kendall's yearly income: $52,000.

Kendall hasn't taken a vacation in 18 years.

He and his wife tried back in 2019. They had a date on the calendar, circled red, September 13, going to Orange Beach, and for months, all they did was daydream about fried oysters, a cooler of margaritas and sitting on the Gulf sand with their feet in the water.

Then, the transmission on his Dodge blew. Two days later, her appendix ruptured. The mechanic and ER bills wiped out their savings. His stomach turned into corded rope. He guzzled Pepto. He remembers walking up to the calendar and marking out the September 13 date, the black ink over the red, his insides feeling like they were in free-fall.

Kendall's been working since he was 12. Cutting firewood for extra money, sweeping floors at the mechanic's, then, the factory floor, then, a regional manufacturer. He'd enrolled in a two-year college, but dropped out when his parents got sick. Took a job. Never looked back.

Through it all, he provided, one way or another: kids in school, clothes and ballgloves and prom dresses when they needed it, presents under the Christmas tree, light bill always paid.

He never asked for a handout.

Never.

And never will, he said.

Always kept working.

Always will.

When he hears that a food pantry gives away food — for free — he feels a burning, an anger. All he does is work and he's still providing. Why the hell can't everyone else? If his family has food, why can't theirs?

He remembers a time when men were respectable. When they shook hands. When work meant something.

What happened to this country?

He sees homeless folks on the street, people with sagging pants, big rings in their noses, holding signs: Hungry.

Not long ago, he ordered a new bumpersticker for his truck. It reads:

The Rich Got Theirs, The Poor Got Welfare, Guess Who's Getting Screwed.

Last month, Kendall and his wife were laying in bed when she mentioned maybe trying again for that vacation.

"Maybe next summer," he says.

They will never make it. Their pipes will burst this winter, then, just before Valentine's Day, Kendall will be rushed to the ER for stomach pains. Doctors will diagnose him with intestinal cancer.

- Alice, a 27-year-old female in north Georgia.

Average cost of land per acre: $10,000.

Her savings account balance: $3503.17.

Alice can't afford the food she grows.

She and her husband Hank farm 18 acres near Dalton. Five of the acres they own, the other 13 are leased. They have cattle, chickens, honeybees and row crops with a hoop house. They sell to three markets a week, along with a CSA that does decently.

Once, she talked Hank into an anniversary dinner at a restaurant that sources beef and vegetables from their farm. It was a lovely evening until the menu came. She saw the prices and was stunned.

Should they walk out? They can't afford this. Almost $45 for a steak? And $12 for a side of mustard greens, mushrooms and onions?

She can't afford the food she grows.

She works part-time at the local elementary school. Hank has a full-time job near Enterprise South. They farm early in the morning, late in the afternoon, all day Saturday, all afternoon Sunday after church.

Their pantry and coolers are always full, but recently, she's caught herself daydreaming about how much money they could get for their five acres.

Developers call once a month, offering her four times more what she paid for her five acres.

- Neal, 73, retired, living in Walker County.

Annual income earned through investments: $203,000.

Net worth of Neal and his wife: $3.5 million.

Neal spent 50 years looking for peace.

Neal worked 60-hour weeks for 20 years, earning his first million by 35. He became one of the region's most innovative and ambitious businessmen. His wife spent three decades as a therapist. They raised three children, all of whom attended private high schools and universities.

Neal serves on boards and attends no fewer than six black-tie galas per year. He knows the invitations come with a catch: we want your money.

Neal's an honest man. His success came from hard work and luck, not cheating. But with it? A sense of never being able to rest. Even on vacation, Neal wasn't. Fifteen years ago, Neal began suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. His doctor told him it was stress.

When Neal turned 60, he bought a fishing cabin up near the river. Hoped it would help. Imagined it as a place he'd go where the stress would float away.

But, if he's honest, he can't shake the agitation, the restlessness, no matter where he is.

He retired last year.

One morning before Sunday School — the pastor recently asked him and his wife to lead the church's upcoming capital campaign — he and another man were about to pour coffee from the Presbyterian Keurig. He mentioned the food bank.

I volunteer there, the man said.

What's it like? Neal asked.

It changed my life, the man replied. Come see for yourself.

So, Neal began volunteering one shift a week. On his first day, he walked into the warehouse and was stunned at the enormity of food, the enormity of need.

One day of volunteering became two, then three. Last spring, Neal was named Volunteer of the Month out of more than 6,500 food bank volunteers.

He helps build the sack-packs, the afterschool boxes that go home with tens of thousands of area children.

Like CJ.

But Neal doesn't know CJ. He never will.

All he knows is that volunteering at the food bank feels like, well, food. It is nourishing, filling.

It isn't the fishing cabin that made him feel better.

It is this.

- Ray, a veteran, formerly homeless, now working in the nonprofit world.

Average monthly trips to a restaurant for an American family: four.

Number of restaurants Ray has visited in 2025: zero.

Ray grew up in the projects. He remembers playing outside and seeing homeless folks tented-up in the woods. He'd buy an extra hot dog from the Kanku's and walk it over to one of them, a man that always seemed the kindest.

He joined the Army, spent years overseas, a paycheck and way-out. Returning home, he started working at a neighborhood community center, then became its director. As an adult, he's back where he began: handing out food, helping those lost in the woods of life.

The community center has a food pantry that serves dozens of neighborhood families, all of whom can't afford groceries without the center's help.

It's one of more than 250 food pantries supported by Chattanooga Area Food Bank.

Once, Ray was asked to speak at a local private school.

He walked into the dining hall — they don't call it a cafeteria — and lost his breath.

He couldn't believe what he was seeing. All this food — pizza, chicken, desserts, fruit, bread, peanut butter, hot corn on the cob, rolls, a salad bar with quinoa, feta cheese, strawberries. And students carried plates piled up, overflowing with food.

"And you can eat as much as you want?" he asked. "Nobody charges you? Nobody says no?"

He began to cry.

"I've never seen anything like this," he said.

The school is just four blocks away from the community center.

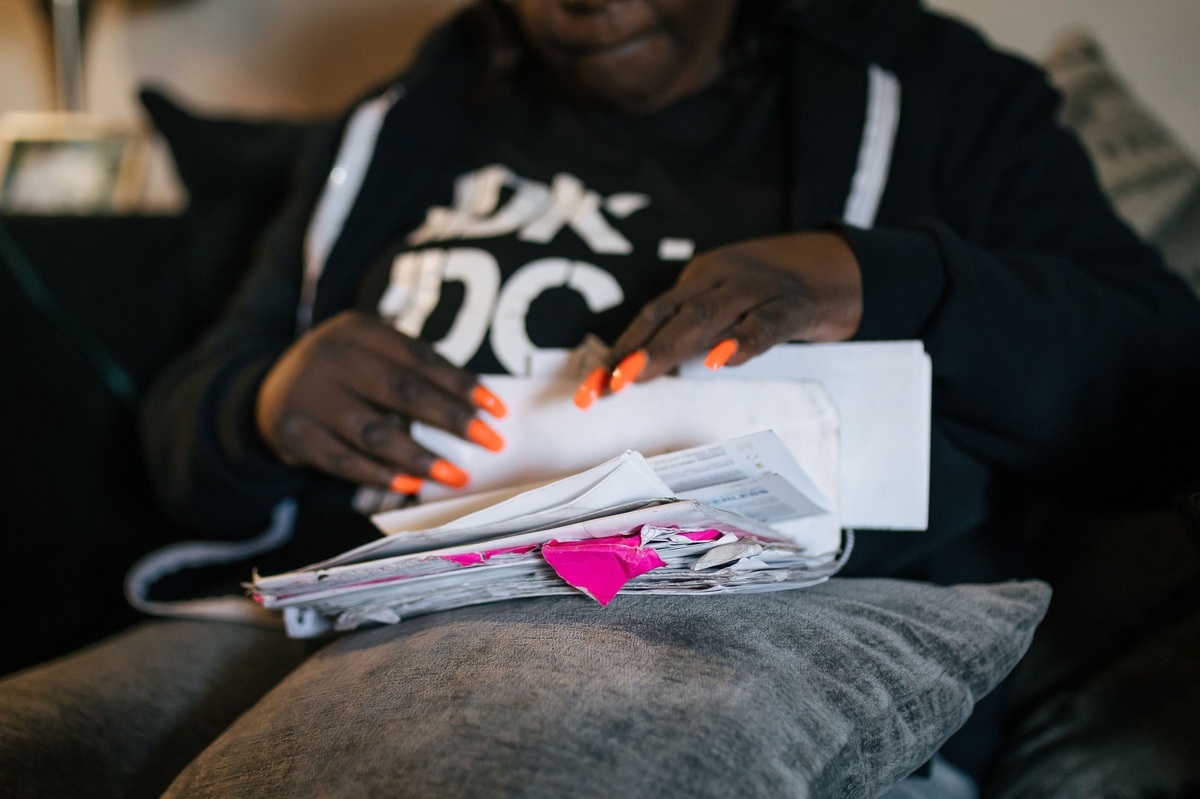

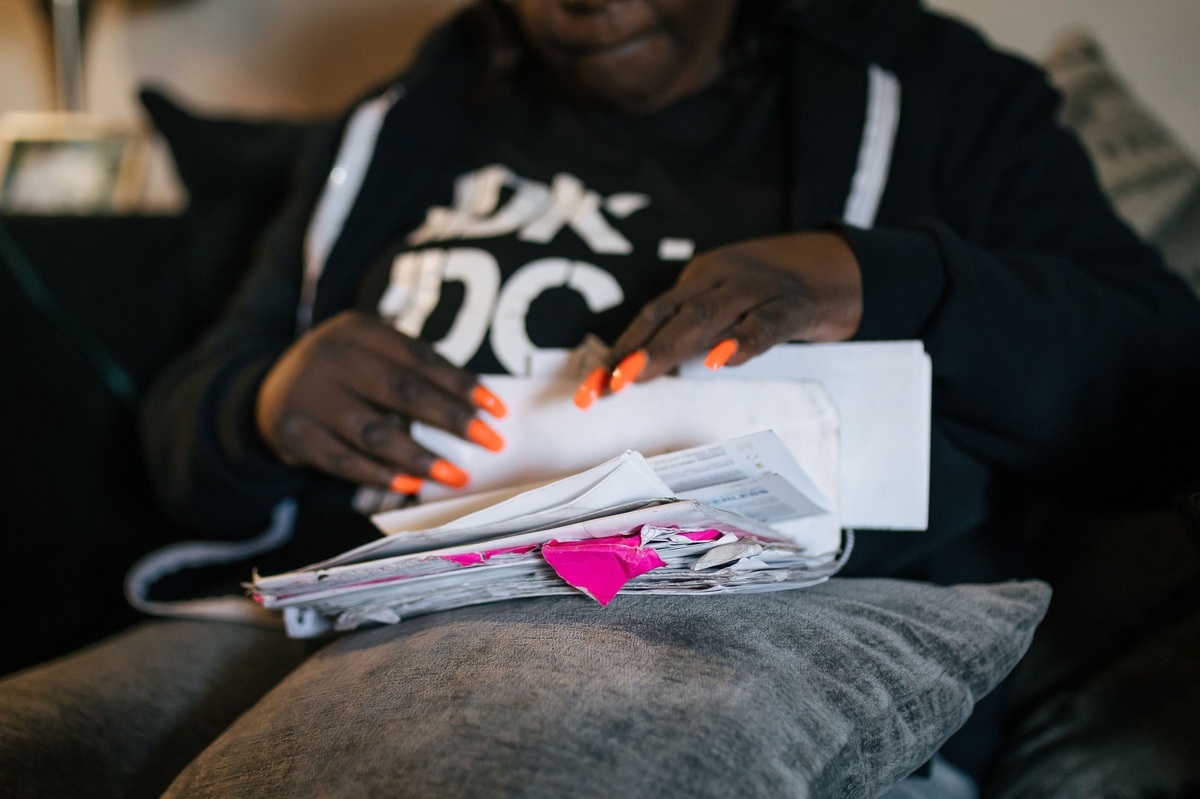

- Angel, 53, a grandmother of three, single, living in Polk County.

Number of jobs currently held: three.

Undiagnosed illnesses, both mental and physical, Angel suffers from: four.

Angel can't pay the bills fast enough. All they do is stack up, and somehow, all she does is work.

Her church offers a weekly food pantry. It's the only thing that keeps her from begging on the street. Her son sleeps on her couch, her daughter and granddaughter sleep in the spare bedroom.

Everybody's working, but, somehow, it won't add up. The landlord just increased rent to $1200. The bathroom leaks. No matter how many times she sprays, she can't kill all the roaches.

She takes care of an elderly woman each day, then sells cell-phone plans on the busy street corner on the weekends.

She prays for others and herself, but, if she's honest, often wonders why.

One day, her neighbor says something about a place called Foxwood. Says the food is free there.

Her fridge is nearly empty. Paycheck's completely gone. She gets directions to Wilcox Boulevard, 35 minutes away, to the Foxwood Food Center. Outside, she's nervous in her car, heart racing, who knows why.

The woman at the desk smiles. Over her shoulder, Angel sees all this food.

It looks just like a grocery store. Folks shopping with carts and buggies.

She turns to the woman, who's still smiling.

"How much? All this food? How much will it cost me?" Angel whispers.

"It's free," the woman said. "It's all for you. It's free."

Angel doesn't know what to say.

"You can come once a month," the woman said. "No questions asked. Can I show you around?"

Angel begins to cry. And pray.

- Eloise, 78, a widow in Marion County.

Years she and Howard were married: 57

Hours in the day she thinks of him: 7

Eloise manages the food pantry at her local Baptist church. When her husband died from Covid, she closed herself off for weeks. It was grief, full-bore, a pain in her chest that would not leave. Her pastor came to visit, then invited her to come volunteer.

Maybe it will help, he said.

Soon, her skills began to flourish there. Attentive, thoughtful, firm when she needs to be, Eloise, a former sixth-grade teacher, soon found herself running the entire food pantry. Collecting food, stocking the shelves, communicating with families, emailing with Chattanooga Area Food Bank staff.

"Howard, if you could only see me now," she says to him, when she visits the cemetery grave.

She's learned how vast hunger is. Young people, old people, working people, they're all affected. Once, a woman, also a widow, who lives in the biggest house in town came to the pantry, just moments before it closed for the day. She was ashamed, embarrassed, Eloise could tell from a mile away.

"You remember her," she said to Howard's gravestone. "She lives in the biggest house in town. Her husband died, too.

"And she's coming in for food? What is this world coming to?"

This isn't the town she grew up in, she thinks some days. Stores are shuttered, lawns weedy and unmowed, young people seem so angry and thin.

She sees the Chattanooga Area Food Bank truck pull up each Monday. Helps unload the boxes of food for the church pantry. Talks with the driver, who says he makes deliveries five days a week to 50 different pantries.

Says it's never enough. Says the pantries need twice as many deliveries.

She visits the cemetery, brings her small lunch to eat next to Howard's grave.

"I miss you," she says. "But I'm doing better."

She started planting a garden once again. A few tomatoes, cucumbers, some lettuce and greens for the fall.

Yesterday, she baked a loaf of banana bread. She pulled it out of the oven and realized: I want to share this.

Then, she knew.

She carried it still warm down the street, wrapped in a soft towel, and knocked on the door of the biggest house in town.

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.

food as a verb thanks our sustaining partner:

food as a verb thanks our story sponsor:

Chattanooga Area Food Bank

Note to reader: these are fictionalized accounts of real people and experiences.

These seven stories are representative of real interviews, encounters, and reporting over the last 20 years. While these portraits are fictionalized, the people behind them — their details and struggles — are not.

We hope these stories offer a respectful rendering of the people impacted by hunger and its different forms while also spotlighting Chattanooga Area Food Bank, which served nearly 17 million meals across 20 counties in 2024.

This is the first in a two-party story series devoted to addressing regional hunger and Chattanooga Area Food Bank's role in responding to that crisis.

Hunger never wears the same face.

- CJ, a 17-year old male living in South Chattanooga.

Average daily caloric needs: 5,000 calories.

Average daily caloric intake: 3,100 calories.

CJ hasn't eaten a piece of fresh fruit in weeks. The last time was early August, the night of the football jamboree, and some folks from a church he'd never heard of had come to the school with plates of dinner kept warm in tin foil to feed the team.

They brought so much food, it filled three tables, stretched end-to-end-to-end: pasta, beans, rice, banana pudding.

It was the banana in the banana pudding. That was the fresh fruit.

They left it out — little candles burning under the tin foil containers — before, during and after the game. His hunger was like an ache, but only ate eight or nine bites of pasta and only two bites of banana pudding.

Food is a strange thing for CJ. The only time he's seen the kitchen being used is during the winter; the stove door's open and his mom's trying to heat the apartment.

His mom works, but jobs change so much he's never fully sure where. His dad died when he was young, before he could even tie his shoes. The closest thing he has to a trusted adult? His coach and his grandmother. But he's got his own kids and she's got cancer.

Most of CJ's meals come from school cafeteria or fast food or the gas station or dollar store.

None of his meals come with a sense of abundance. CJ can't remember the last time he ever ate without fear.

Fear there won't be enough.

Fear that eating will make him even hungrier.

Psychologists and social workers often use the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) as a study that evaluates trauma and dysfunction. He'd score through the roof.

But CJ doesn't know that. Doesn't know the terms disassociation or complex trauma. He just knows — even barely — that life feels so numb, his head without a body, like a fog that makes him want to sleep and not wake.

CJ has an eating disorder. Normally associated with middle or upper class teens, eating disorders also affect people like CJ: he refuses to eat, afraid that doing so will make him even hungrier.

Each week, Chattanooga Area Food Bank supports food pantries in schools and sack-packs for the weekend. Across 20 counties, the food bank distributes more than 160,000 meals for children and teens each year.

Like CJ.

But it's never enough.

- Kendall, 63, living in Hamilton County.

Approximate average median income: $75,000.

Kendall's yearly income: $52,000.

Kendall hasn't taken a vacation in 18 years.

He and his wife tried back in 2019. They had a date on the calendar, circled red, September 13, going to Orange Beach, and for months, all they did was daydream about fried oysters, a cooler of margaritas and sitting on the Gulf sand with their feet in the water.

Then, the transmission on his Dodge blew. Two days later, her appendix ruptured. The mechanic and ER bills wiped out their savings. His stomach turned into corded rope. He guzzled Pepto. He remembers walking up to the calendar and marking out the September 13 date, the black ink over the red, his insides feeling like they were in free-fall.

Kendall's been working since he was 12. Cutting firewood for extra money, sweeping floors at the mechanic's, then, the factory floor, then, a regional manufacturer. He'd enrolled in a two-year college, but dropped out when his parents got sick. Took a job. Never looked back.

Through it all, he provided, one way or another: kids in school, clothes and ballgloves and prom dresses when they needed it, presents under the Christmas tree, light bill always paid.

He never asked for a handout.

Never.

And never will, he said.

Always kept working.

Always will.

When he hears that a food pantry gives away food — for free — he feels a burning, an anger. All he does is work and he's still providing. Why the hell can't everyone else? If his family has food, why can't theirs?

He remembers a time when men were respectable. When they shook hands. When work meant something.

What happened to this country?

He sees homeless folks on the street, people with sagging pants, big rings in their noses, holding signs: Hungry.

Not long ago, he ordered a new bumpersticker for his truck. It reads:

The Rich Got Theirs, The Poor Got Welfare, Guess Who's Getting Screwed.

Last month, Kendall and his wife were laying in bed when she mentioned maybe trying again for that vacation.

"Maybe next summer," he says.

They will never make it. Their pipes will burst this winter, then, just before Valentine's Day, Kendall will be rushed to the ER for stomach pains. Doctors will diagnose him with intestinal cancer.

- Alice, a 27-year-old female in north Georgia.

Average cost of land per acre: $10,000.

Her savings account balance: $3503.17.

Alice can't afford the food she grows.

She and her husband Hank farm 18 acres near Dalton. Five of the acres they own, the other 13 are leased. They have cattle, chickens, honeybees and row crops with a hoop house. They sell to three markets a week, along with a CSA that does decently.

Once, she talked Hank into an anniversary dinner at a restaurant that sources beef and vegetables from their farm. It was a lovely evening until the menu came. She saw the prices and was stunned.

Should they walk out? They can't afford this. Almost $45 for a steak? And $12 for a side of mustard greens, mushrooms and onions?

She can't afford the food she grows.

She works part-time at the local elementary school. Hank has a full-time job near Enterprise South. They farm early in the morning, late in the afternoon, all day Saturday, all afternoon Sunday after church.

Their pantry and coolers are always full, but recently, she's caught herself daydreaming about how much money they could get for their five acres.

Developers call once a month, offering her four times more what she paid for her five acres.

- Neal, 73, retired, living in Walker County.

Annual income earned through investments: $203,000.

Net worth of Neal and his wife: $3.5 million.

Neal spent 50 years looking for peace.

Neal worked 60-hour weeks for 20 years, earning his first million by 35. He became one of the region's most innovative and ambitious businessmen. His wife spent three decades as a therapist. They raised three children, all of whom attended private high schools and universities.

Neal serves on boards and attends no fewer than six black-tie galas per year. He knows the invitations come with a catch: we want your money.

Neal's an honest man. His success came from hard work and luck, not cheating. But with it? A sense of never being able to rest. Even on vacation, Neal wasn't. Fifteen years ago, Neal began suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. His doctor told him it was stress.

When Neal turned 60, he bought a fishing cabin up near the river. Hoped it would help. Imagined it as a place he'd go where the stress would float away.

But, if he's honest, he can't shake the agitation, the restlessness, no matter where he is.

He retired last year.

One morning before Sunday School — the pastor recently asked him and his wife to lead the church's upcoming capital campaign — he and another man were about to pour coffee from the Presbyterian Keurig. He mentioned the food bank.

I volunteer there, the man said.

What's it like? Neal asked.

It changed my life, the man replied. Come see for yourself.

So, Neal began volunteering one shift a week. On his first day, he walked into the warehouse and was stunned at the enormity of food, the enormity of need.

One day of volunteering became two, then three. Last spring, Neal was named Volunteer of the Month out of more than 6,500 food bank volunteers.

He helps build the sack-packs, the afterschool boxes that go home with tens of thousands of area children.

Like CJ.

But Neal doesn't know CJ. He never will.

All he knows is that volunteering at the food bank feels like, well, food. It is nourishing, filling.

It isn't the fishing cabin that made him feel better.

It is this.

- Ray, a veteran, formerly homeless, now working in the nonprofit world.

Average monthly trips to a restaurant for an American family: four.

Number of restaurants Ray has visited in 2025: zero.

Ray grew up in the projects. He remembers playing outside and seeing homeless folks tented-up in the woods. He'd buy an extra hot dog from the Kanku's and walk it over to one of them, a man that always seemed the kindest.

He joined the Army, spent years overseas, a paycheck and way-out. Returning home, he started working at a neighborhood community center, then became its director. As an adult, he's back where he began: handing out food, helping those lost in the woods of life.

The community center has a food pantry that serves dozens of neighborhood families, all of whom can't afford groceries without the center's help.

It's one of more than 250 food pantries supported by Chattanooga Area Food Bank.

Once, Ray was asked to speak at a local private school.

He walked into the dining hall — they don't call it a cafeteria — and lost his breath.

He couldn't believe what he was seeing. All this food — pizza, chicken, desserts, fruit, bread, peanut butter, hot corn on the cob, rolls, a salad bar with quinoa, feta cheese, strawberries. And students carried plates piled up, overflowing with food.

"And you can eat as much as you want?" he asked. "Nobody charges you? Nobody says no?"

He began to cry.

"I've never seen anything like this," he said.

The school is just four blocks away from the community center.

- Angel, 53, a grandmother of three, single, living in Polk County.

Number of jobs currently held: three.

Undiagnosed illnesses, both mental and physical, Angel suffers from: four.

Angel can't pay the bills fast enough. All they do is stack up, and somehow, all she does is work.

Her church offers a weekly food pantry. It's the only thing that keeps her from begging on the street. Her son sleeps on her couch, her daughter and granddaughter sleep in the spare bedroom.

Everybody's working, but, somehow, it won't add up. The landlord just increased rent to $1200. The bathroom leaks. No matter how many times she sprays, she can't kill all the roaches.

She takes care of an elderly woman each day, then sells cell-phone plans on the busy street corner on the weekends.

She prays for others and herself, but, if she's honest, often wonders why.

One day, her neighbor says something about a place called Foxwood. Says the food is free there.

Her fridge is nearly empty. Paycheck's completely gone. She gets directions to Wilcox Boulevard, 35 minutes away, to the Foxwood Food Center. Outside, she's nervous in her car, heart racing, who knows why.

The woman at the desk smiles. Over her shoulder, Angel sees all this food.

It looks just like a grocery store. Folks shopping with carts and buggies.

She turns to the woman, who's still smiling.

"How much? All this food? How much will it cost me?" Angel whispers.

"It's free," the woman said. "It's all for you. It's free."

Angel doesn't know what to say.

"You can come once a month," the woman said. "No questions asked. Can I show you around?"

Angel begins to cry. And pray.

- Eloise, 78, a widow in Marion County.

Years she and Howard were married: 57

Hours in the day she thinks of him: 7

Eloise manages the food pantry at her local Baptist church. When her husband died from Covid, she closed herself off for weeks. It was grief, full-bore, a pain in her chest that would not leave. Her pastor came to visit, then invited her to come volunteer.

Maybe it will help, he said.

Soon, her skills began to flourish there. Attentive, thoughtful, firm when she needs to be, Eloise, a former sixth-grade teacher, soon found herself running the entire food pantry. Collecting food, stocking the shelves, communicating with families, emailing with Chattanooga Area Food Bank staff.

"Howard, if you could only see me now," she says to him, when she visits the cemetery grave.

She's learned how vast hunger is. Young people, old people, working people, they're all affected. Once, a woman, also a widow, who lives in the biggest house in town came to the pantry, just moments before it closed for the day. She was ashamed, embarrassed, Eloise could tell from a mile away.

"You remember her," she said to Howard's gravestone. "She lives in the biggest house in town. Her husband died, too.

"And she's coming in for food? What is this world coming to?"

This isn't the town she grew up in, she thinks some days. Stores are shuttered, lawns weedy and unmowed, young people seem so angry and thin.

She sees the Chattanooga Area Food Bank truck pull up each Monday. Helps unload the boxes of food for the church pantry. Talks with the driver, who says he makes deliveries five days a week to 50 different pantries.

Says it's never enough. Says the pantries need twice as many deliveries.

She visits the cemetery, brings her small lunch to eat next to Howard's grave.

"I miss you," she says. "But I'm doing better."

She started planting a garden once again. A few tomatoes, cucumbers, some lettuce and greens for the fall.

Yesterday, she baked a loaf of banana bread. She pulled it out of the oven and realized: I want to share this.

Then, she knew.

She carried it still warm down the street, wrapped in a soft towel, and knocked on the door of the biggest house in town.

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.